Laurie's Blogs.

Mar 2024

Vestibular Dogs and Return to Sport – PART 1

An interesting question came up as it pertains to dogs that have recovered from vestibulitis and participation in sports. Should we be concerned? Is there anything that can or should be done to help these dogs in regards to warm up or injury prevention?

GREAT Question!!!

To answer that question, I first dove into the literature, because we need to be on the same page in regard to what we are talking about. Two very interesting and useful studies came up.

1. Harrison E, Grapes NJ, Volk HA, De Decker S. Clinical reasoning in canine vestibular syndrome: Which presenting factors are important? Vet Rec. 2021 Mar;188(6):e61.

Out of 239 dogs sourced retrospectively, 95% of dogs were represented by eight conditions: idiopathic vestibular disease (n = 78 dogs), otitis media interna (n = 54), meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (n = 35), brain neoplasia (n = 26), ischaemic infarct (n = 25), intracranial empyema (n = 4), metronidazole toxicity (n = 3) and neoplasia affecting the middle ear (n = 3).

“Idiopathic vestibular disease was associated with higher age, higher bodyweight, improving clinical signs, pathological nystagmus, facial nerve paresis, absence of Horner's syndrome and a peripheral localisation. Otitis media interna was associated with younger age, male gender, Horner's syndrome, a peripheral localisation and a history of otitis externa. Ischaemic infarct was associated with older age, peracute onset of signs, absence of strabismus and a central localization.”

2. Orlandi R, Gutierrez-Quintana R, Carletti B, Cooper C, Brocal J, Silva S, Gonçalves R. Clinical signs, MRI findings and outcome in dogs with peripheral vestibular disease: a retrospective study. BMC Vet Res. 2020 May 25;16(1):159.

This study aimed to describe the clinical signs and MRI findings, causes and outcomes in dogs diagnosed with peripheral vestibular disease.

“One hundred eighty-eight patients were included in the study with a median age of 6.9 years (range 3 months to 14.6 years). Neurological abnormalities included head tilt (n = 185), ataxia (n = 123), facial paralysis (n = 103), nystagmus (n = 97), positional strabismus (n = 93) and Horner syndrome (n = 7). The most prevalent diagnosis was idiopathic vestibular disease (n = 128), followed by otitis media and/or interna (n = 49), hypothyroidism (n = 7), suspected congenital vestibular disease (n = 2), neoplasia (n = 1) and cholesteatoma (n = 1). Long-term follow-up revealed persistence of head tilt (n = 50), facial paresis (n = 41) and ataxia (n = 6) in some cases.”

Key findings / discussion points:

17.6% of the dogs had a reoccurrence

Increased age was associated with a mild increased chance of idiopathic geriatric vestibulitis diagnosis

History of previous vestibular episodes was associated with increased likelihood of resolution

Contrast enhancement of cranial nerves VII and/or VIII on MRI was associated with a decreased chance of resolution of the clinical signs.

REHAB Indications

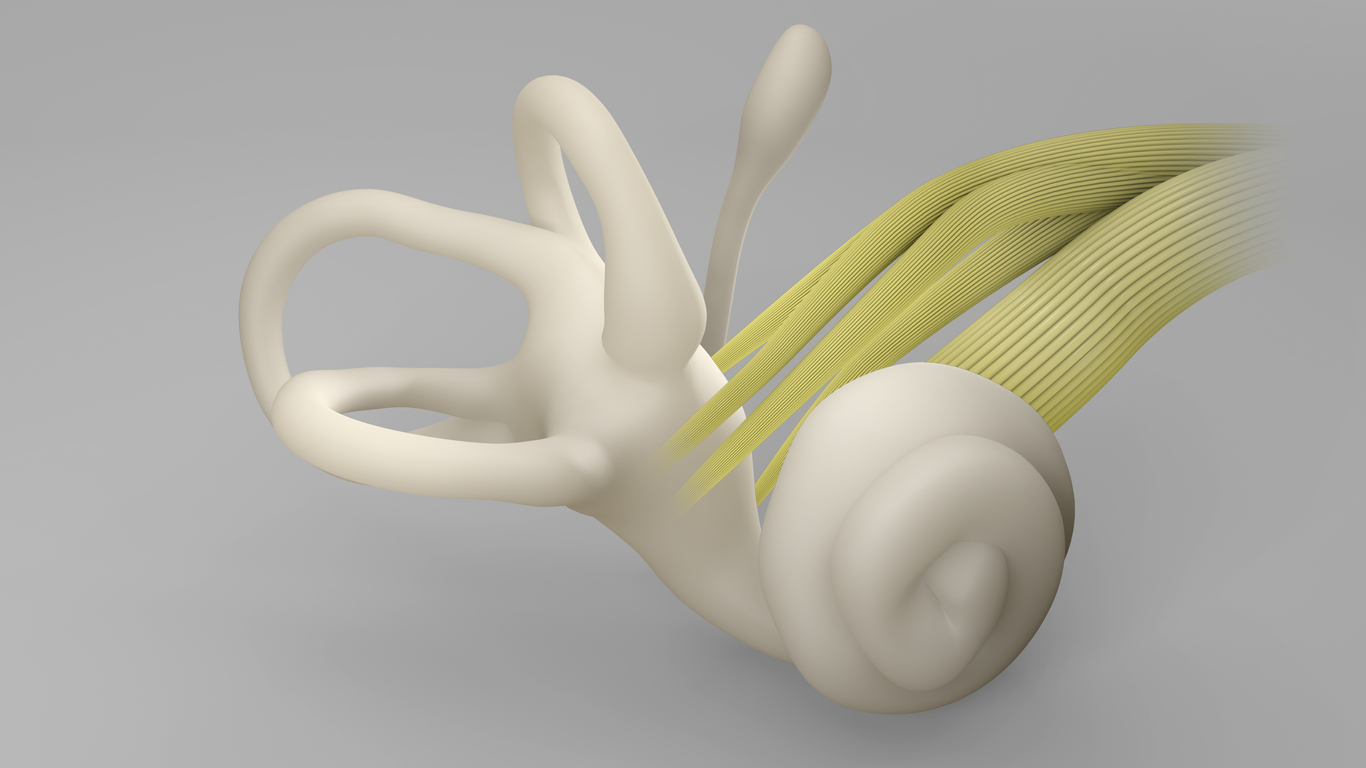

We, on the rehab front, are likely the ones actively treating the idiopathic geriatric vestibulitis (IGV) cases. They present (and respond) just like benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) in people. BPPV is a condition whereby an otolith (a tiny crystal located on a hair follicle in the saccule of the inner ear) becomes dislodged and enters a semicircular canal, thus causing the vestibular signs and symptoms. To assess for this, the Dix Hallpike maneuver or side lie technique is utilized. The specific change in postural positioning sets off symptoms (nausea) and signs (nystagmus). The other conditions associated with vestibulitis are not affected by position. This is a hallmark of BPPV and IGV. The other conditions associated with peripheral vestibular disease listed above are not affected by sudden postural changes.

IF we have IGV, then we treat it with positional techniques at first and follow up with balance exercises and eye coordination exercises.

IF the dog does not show evidence of altered signs and symptoms with the positioning techniques, then further investigation is warranted, and appropriate treatment required (i.e. antibiotics for an inner ear infection).

IF a dog has concurrent facial paralysis, then a viral correlation might be causal to both the vestibulitis and facial paralysis.

With all of this information at hand, we can next look at whether or not an animal can partake in sporting activities safely following a diagnosis of peripheral vestibulitis. How should we test competency and safety for return to sport (or training) and is there anything that an owner should do prior to competition to help minimize risks upon return to sport? Give me a week to think about it and I’ll come back with my thoughts and ideas!

Until then…

Cheers! Laurie